Only Connect

Story has never been more fashionable. Everything from insurance sales to football to toothpaste is sold using some kind of story.

But what do we really mean by “story”? And how can it help in designing museums and exhibitions? There’s a very famous short story dubiously attributed to the American writer Ernest Hemingway

For Sale: Baby Shoes, Never Worn

This kind of short story is known as “flash fiction” or, in Chinese it’s called “smoke long” because the story only lasts as long as it takes the listener to finish a cigarette – although you’d have to be a pretty fast smoker to get through a cigarette in six words!

These six words are a helpful reminder of the basic ingredients of story and what I consider to be the basic ingredients of a good exhibition. You can see the first four words are neutral facts: For Sale: Baby Shoes. It’s really the two final words that make it a story.

Those two words: “Never Worn”, suddenly deliver a whole world of pain that is not present in the first four. These two words make meaning and create an emotional connection for the reader.

It is this connection which is so vital in good story-telling and so hard to achieve in designing exhibitions which have to appeal to a wide audience. John Steinbeck talks about the need for good stories to create connections for everyone:

“If a story is not about the hearer he will not listen. And here I make a rule - a great and interesting story is about everyone or it will not last.”

You’re probably thinking that’s a very difficult thing to achieve. But I think what Steinbeck means is that a good story has to offer hooks for different people and if it is to have impact it must connect with each person’s own story in some way.

Shaping Stories

Where were you on 11th September 2001 - otherwise known as 9/11? The day Al Quaeda attacked the World Trade Center in New York City?

I remember very clearly where I was. Standing on a former battlefield in northern France with a group of archaeologists. They were using new DNA techniques to identify the remains of unknown soldiers killed during World War One. It was a bleak, cold day and the landscape around me was desolate. My colleague’s mobile phone rang and I was annoyed with him for answering because the place where we stood felt sacred and his phone seemed to violate the memories of what had happened there.

“Twin towers; airplanes; attacks; collapse”….the disconnected words continued to tumble from his mouth and slowly the horror began to dawn. I actually thought “World War Three is beginning and I’m stuck on a battlefield from World War One”.

Now, 14 years later, a new museum has opened on the site of the World Trade Center. The National September 11th Memorial Museum is designed to remember those who died and seeks to tell the complex story of what happened that day. Stories don’t get much more powerful than 9/11 but, unlike our story about the baby shoes, what happened on September 11th is massively complicated and it takes great skill to shape it into pieces that are manageable for visitors from all over the world to connect with.

I’d heard very differing opinions about the Memorial Museum. This is inevitable with almost any museum but particularly so with such a politically complex and emotionally charged one. While I found the spaces to be shockingly real – still ringing with the sounds of a global theatre of war, hatred and irreconcilable difference, others have told me they found the museum alienating, difficult to relate to and sanitised.

These arguments are interesting in themselves as they show how subjective any museum experience can be. But here I want to explore five ideas that grew from my experience at the 9/11 Museum and to show how they can be applied to shaping stories in space.

The Power of the Real

The National September 11th Memorial Museum is a great example of where the space itself tells a very powerful story. By simply arriving at Ground Zero and seeing the Memorial Pools on the footprint of each tower of the former World Trade Center you are embarking on a narrative journey. Some people feel this is enough and are deeply moved by the simplicity of the waterfalls, by the names inscribed on the bronze walls.

But for those who want to venture down into the foundations of the World Trade Center there is a powerful narrative expressed in the very fabric of the foundations, the remnants of the steelwork, the retaining wall of the Hudson River.

All these elements of “the real” create an incredible theatre within which the detail of the story unfolds. This “power of the real” is a great virtue in creating narratives as the place itself tells a story before you even begin to communicate the detail.

The Journey

To visit the 9/11 Memorial Museum is to go on a physical journey as well as an emotional one and I was really interested to understand how these two relate in designing spaces for exhibitions. Where narrative and physical spaces work together each reinforces the other and here at the 9/11 Museum I felt they were fairly well aligned.

The visit begins with a steep descent - a powerful threshold with all its associations with death and loss but also has a very tangible message because the museum itself is situated within the foundations of the World Trade Center. So as I descend further into what’s called Foundation Hall I get a sense of the height of these buildings and of the great abyss into which they fell on that terrible day.

Part of the descent takes me alongside the Vesey Street staircase that was one of the few means of exit for people escaping the wreckage. During the construction of the museum this staircase had been scheduled for demolition but those people whose lives had been saved by it protested vehemently and the staircase was saved from demolition and incorporated into the museum.

Making Meaning

The opening exhibit of the museum reminded me of John Steinbeck’s advice that a “great story must be about the listener”. While most of the visitors to the 9/11 Museum were not directly involved, the designers nonetheless created connections to allow everyone to bring their own story of that day. The opening exhibit shows how people all around the world were affected by the attacks. Right from the start I am drawn in, I’m told “it’s not just our story, this story is also about you”. As the visit continues this message is reinforced. We are all part of this conflict and as human beings we can all participate in its resolution.

Narrative Layers

A story as complex and as emotionally upsetting as 9/11 presents a real design challenge – just how do you go about layering so many complex narratives without baffling or overwhelming the visitor?

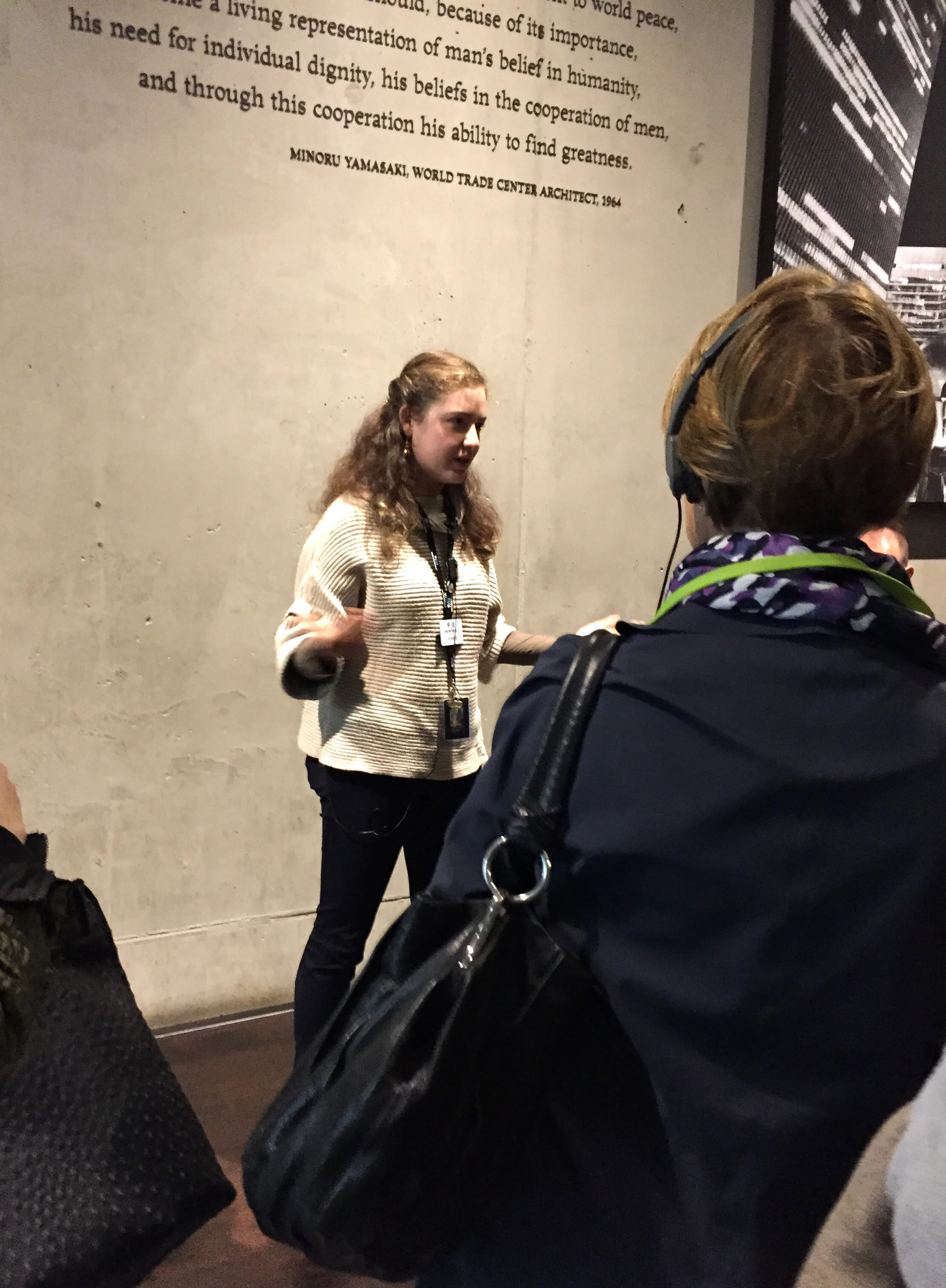

I choose to follow a tour where the guide speaks to the group through individual headsets. This allows the guide to speak quietly, avoids any imposition on other visitors and gives me the freedom to wander as I please while still being able to hear the tour guide. We are also invited to switch off our headsets at any point if the story becomes too overwhelming.

The strength of the guide was to lead us with her voice from a tiny detail in a fire truck to a huge philosophical thought about transformation without our really noticing it. The layers of narrative were visible if we chose to analyse them but actually seamless if we chose to just go with the flow. I was particularly impressed with this overarching narrative around transformation which was expressed through many different stories, some heart-wrenching and tragic, others uplifting and positive. The lesson here is the power of a big narrative which creates the lens through which the detail can be viewed. It provides a hook upon which to hang so many different layers throughout the visit and allows different people to connect on different levels.

Imagination

Finally I think it’s really vital to remember that “narrative” is not always expressed by a linear description of a definable sequence of events but can sometimes be more powerful when it is simply be about firing the imagination or making a visceral in new or unexpected ways. I’m thinking of exhibitions or artworks where the object itself embodies the meaning and to see it is to submit to what it provokes inside you rather than to seek a long explanation.

When it works this can be the most powerful form of storytelling because the listener is creating the story for themselves inside their own bodies and minds. The memorial pools are a great example of this as is the art work in Foundation Hall. These letters spell out a line from a poem by the ancient Roman poet Virgil:

“No Day Shall Erase Thee from the Memory of Time.”

The letters are made of steel from the wreckage of the World Trade Center. The blue ceramic tiles represent the bright colour of the sky that September morning in New York while their varied hues represent each individual who lost their lives on that day. The story of the day dwells within the very fabric of this artwork.

So for me narrative is not about a linear story but rather a means to create connection and make meaning. It’s the difference between information and communication as or, author Sydney J Harris says:

“Information is giving out; communication is getting through.”